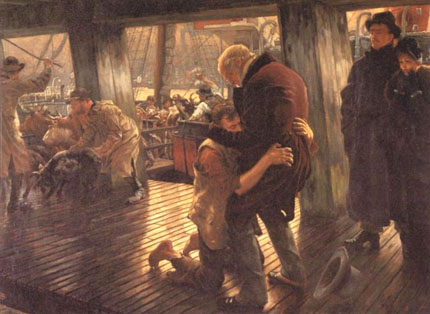

The Forgiving Father

In tomorrow's Gospel reading Jesus tells one of his best known parables, The Prodigal Son. Noted Episcopal preacher Barbara Brown Taylor once preached a sermon on this text called The Parable of the Disfunctional Family. I have seen some fellow preachers passing this sermon around this week with awe. My friend Kit writing that a sermon like this one makes her want to just stand in silence in the pulpit. Barbara Brown Taylor wrote in part,

The beauty of a really good parable—in the case of the prodigal son, perhaps the most beloved parable of all time—is that it meets generations of listeners wherever they are: in first century Palestine, in fourth century Rome, in sixteenth century Geneva, or in twenty-first century Chicago. Everyone has a weird family. Everyone has at least thought about running away from home. And whether or not you happen to have one yourself, almost everyone knows what a pain a sibling can be—especially when there are only two of you, so that the “good child/bad child” thing hovers over you no matter which one you happen to be at any given time. For these reasons and more, the parable of the prodigal son stays young no matter how old it is, giving all kinds of people all kinds of ways to make the story their own.She goes on to draw more from the story in a beautifully written sermon. The full text of her sermon is online here: The Parable of the Disfunctional Family.

The problem with a really good parable—especially one as beloved as this one--is that it can become limp from too much handling. Like the velveteen rabbit, it can lose its eyes, its whiskers, and a lot of its stuffing, until it conforms to the arms of whoever picks it up. After a while, you hardly have to hold it anymore. You can just sling it over your wrist, with the head on one side and the body on the other, trusting it to stay put while you go about your business. That’s how you know you don’t have a live parable anymore, capable of leaping from your arms and leading you out to where you did not mean to go. You have a domestic pet instead, as captive to you as you are to your culture.

In twenty-first century Chicago, there is nothing remarkable about a young man deciding to leave his father’s home, where he will never be anything but the baby brother, to go seek his fortune in the world. This is so American that it’s hard to remember this boy is not from southern Illinois. From Daniel Boone to Lance Armstrong, the rugged individual is a national icon. The younger son did what young men are born to do. He may have hurt his father in the process, but his father understood, since he probably did the same thing himself. The difference was that the father made good and the son did not.By failing at his individuation project, the son fell short of the American ideal, but all was not lost. In place of worldly success, he won wisdom, returning home to beg his father’s forgiveness—which his father gave him before he asked. The boy who was lost to his father was found. The son who was dead came back to life, and though he still had some things to work out with his elder brother, he was restored to his family and to his father’s love, sadder but wiser for all that he had brought upon himself.

Told in this way, the parable is indeed the parable of the prodigal son—a story about the vastness of a father’s love, available to a wastrel son who returns home with true repentance in his heart. The way most Christians tell it, it is about our individual relationships with God. When we decide to go home and say we’re sorry, we too can be sure that a banquet awaits us—the improbable feast given in our honor by a father whose divine grace exceeds all human reason.

That’s a perfectly good story. It is also, I think, an American Protestant one, which is fine for those who want Jesus to be more like us. If we want to be more like him, however, then it is worth wondering what this story might have meant to a Middle Eastern audience hearing it from a Middle Eastern storyteller in the middle of the first century. What does Jesus know about the dynamics of this story that we do not know, because he told it in a different world?

Labels: Gospel reading

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home