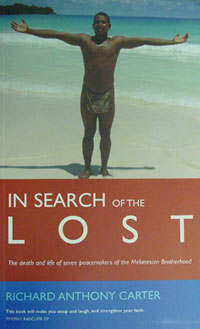

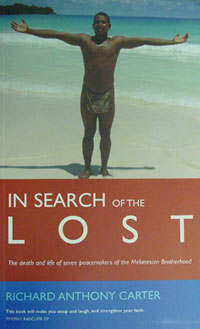

The Rev. Richard Anthony Carter's book,

In Search of the Lost

, on the death and life of seven peacemakers of the Melanesian Brotherhood is a profoundly good book.

In tomorrow's religion column for the

Tribune & Georgian I'll tell the extraordinary story of how I came to own a copy. Today, I'll give Irenic Thoughts readers a sneak peek at that column:

Unseen connections more binding

than those we seeI am not given to crying. I do cry. But rarely. So I was taken aback to find myself crying in the Kingsland Post Office a couple of weeks ago. But there in my mail was proof of an intangible connection shared with a man I had never met who had lived in the south Pacific when that connection was forged.

It all began in 2003 when I was preparing a group of teens and adults to make a public profession of their faith in Jesus. I find it important on occasions like this to connect Christians here in south Georgia to very different experiences of our Christian faith in other parts of the world. For example, I had previously explored with a different group the experience of being Christian in the Sudan, where our sisters and brothers in the faith suffer persecution.

But in early August of 2003, what was on my mind was the missing members of the Melanesian Brotherhood. And I read to the group something of the situation there. Internal struggles on the island of Guadalcanal had come to a head with armed conflict between two rival factions, one representing natives of Guadalcanal, the other made up of migrants from the nearby island of Malaita. The members of the Melanesian Brotherhood were interceding for peace in the conflict.

The Melanesian Brotherhood is a most interesting group in and of itself. Founded in 1925 by a Melanesian who wanted a religious order indigenous to his peoples. The Brotherhood kept the typical vows of poverty, chastity and obedience common to monks and nuns, but they did it in an atypical way as the norm was for these vows to be for a time and the brothers would later return to their homes, marry and raise a family. In this way, the Melanesian Brotherhood became salt to the south Pacific and added savor to the Christian experience of the islanders.

The Brothers travel two by two, bare foot and with a staff in hand to spread the Gospel and to intercede as needed in prayer and in direct aid as well in a variety of situations. So when armed conflict came to Guadalcanal, it was natural that the brothers placed themselves into the situation. In May 2000, they sent a group to camp in the no man’s land between enemy lines. The letter they carried to both militant groups read in part,

In the name of Jesus Christ we appeal to you: stop the killing, stop the hatred, stop the payback. Those people you hate and kill are your own Solomon Island brother.

Then they stayed for four months in a no man’s land between armed and angry militants and forbade them in the name of God to advance from the barricades. Peace did come. But in the truce neither side disarmed. So by 2002, the Melanesian Brotherhood was working to collect weapons and dump them in the deep sea.

Harold Keke was the leader of the native Guadalcanal group. He refused to disarm and so while many individuals did turn over their weapons, neither of the two main factions did and the threat of violence loomed large. Three brothers were sent with a letter from Anglican Archbishop Ellison Pogo to Harold Keke. The militant leader was not in his camp. Two brothers left, but a third Nathaniel Sodo remained. He knew Keke’s brother and thought he could intercede and make a difference. Time passed. Sodo did not return. On Easter Day 2003, one of Keke’s men left the encampment, went to the Solomon Islands Broadcasting Company and said the Sodo had been killed.

As rumors were run wild in those days, a group of six brothers was dispatched by boat to go to the Weathercoast, where Keke was encamped and to discover the truth and if need be to bring back Sodo’s body. Those six brothers did not return. It was during that wait for news that we began to pray in Kingsland. On August 9, the devastating news came around the world that all seven brothers had been killed by Keke’s men. We continued to pray for the Melanesian Brotherhood. Inexplicably I felt a strong connection through prayer to these peacemakers killed for their non-violent attempts to disarm their island.

The bodies were brought back and buried. The grief that poured out throughout the Solomon Islands brought an end to the conflict as Keke turned himself in. The Solomon Islanders would not associate themselves with those who would kill members of their beloved Melanesian Brotherhood.

Time passed. In the fall of 2004, I preached a sermon about the connectedness we share with other Christians. I used the writings of Brother Richard Carter, chaplain of the Melanesian Brotherhood and chief spokesman in the crisis. He had written eloquently of how the prayers of others around the world had kept them afloat in what seemed to be a sea of unbearable grief.

Two weeks ago as I opened mail at the Kingsland Post Office, there was a package from Brother Carter. It contained a copy of his book,

In Search of the Lost, which tells of the experience of the brothers. A note told me that someone had shared my sermon with him after having run across it on the Internet. He wrote, “I am sending you a copy [of the book] with my very best wishes and deep gratitude for your prayers and that of your church at that time.”

The letter closed the loop. I had been here praying with others, feeling like we were connected to this situation by our God who was present both to us and the members of the Melanesian Brotherhood. In writing and sending a book, Brother Carter showed that the connection forged between Guadalcanal and Kingsland was something unseen and yet somehow tangible. What connected was not the Internet. That was only the vehicle for God to reveal the connection that existed through prayer.

So many times we pray and never hear word of what has happened. Yet, we walk by faith and not by sight and trust that God not only hears our prayers, but desires that we pray as much for what those prayers do for us in connecting us to the needs of others as for what those prayers do for God.

(The Rev. Frank Logue is pastor of King of Peace Episcopal Church in Kingsland. The text of the sermon referenced in this column is online at

The Great Cloud of Witnesses)

Labels: In Search of the Lost, Melanesian Brotherhood, prayer

In

In

The

The  The New Testament words for the orders of ministry—Bishop (Episkopos), Priest (Presbuteros) and Deacon (Diakonos)—show our current Episcopal Church usage of "priest" as shown in the images of priesthood blog applies to the presbuteros, or presbyters, which means "elders." So the blog and its look at images of the presbuteros, commonly referred to as priests in the Episcopal Church today is a great look at the range of meaning for that term. I just want to also uphold that we have four orders of ministry in the Episcopal Church: Lay persons, Bishops, Priests and Deacons. And the laity are an integral part of the Kingdom of Priests who serve God.

The New Testament words for the orders of ministry—Bishop (Episkopos), Priest (Presbuteros) and Deacon (Diakonos)—show our current Episcopal Church usage of "priest" as shown in the images of priesthood blog applies to the presbuteros, or presbyters, which means "elders." So the blog and its look at images of the presbuteros, commonly referred to as priests in the Episcopal Church today is a great look at the range of meaning for that term. I just want to also uphold that we have four orders of ministry in the Episcopal Church: Lay persons, Bishops, Priests and Deacons. And the laity are an integral part of the Kingdom of Priests who serve God.

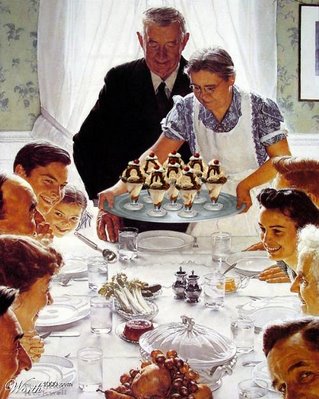

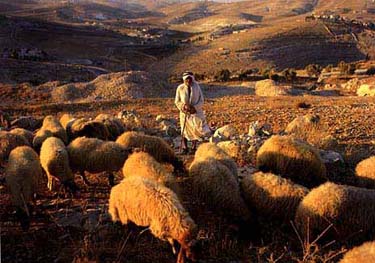

They are words for parents and teachers, workers in the lab and those who tend the ground to raise crops, those who sit at computers performing their work and those who nurse the sick and troubled . . . for all of God's people everywhere. God's lambs and sheep are everywhere, and our Lord calls us to "tend them, to feed them, to become his presence among and for them," feeding them with the word that we, ourselves, have heard: "Peace be with you."

They are words for parents and teachers, workers in the lab and those who tend the ground to raise crops, those who sit at computers performing their work and those who nurse the sick and troubled . . . for all of God's people everywhere. God's lambs and sheep are everywhere, and our Lord calls us to "tend them, to feed them, to become his presence among and for them," feeding them with the word that we, ourselves, have heard: "Peace be with you."

As rumors were run wild in those days, a group of six brothers was dispatched by boat to go to the Weathercoast, where Keke was encamped and to discover the truth and if need be to bring back Sodo’s body. Those six brothers did not return. It was during that wait for news that we began to pray in Kingsland. On August 9, the devastating news came around the world that all seven brothers had been killed by Keke’s men. We continued to pray for the Melanesian Brotherhood. Inexplicably I felt a strong connection through prayer to these peacemakers killed for their non-violent attempts to disarm their island.

As rumors were run wild in those days, a group of six brothers was dispatched by boat to go to the Weathercoast, where Keke was encamped and to discover the truth and if need be to bring back Sodo’s body. Those six brothers did not return. It was during that wait for news that we began to pray in Kingsland. On August 9, the devastating news came around the world that all seven brothers had been killed by Keke’s men. We continued to pray for the Melanesian Brotherhood. Inexplicably I felt a strong connection through prayer to these peacemakers killed for their non-violent attempts to disarm their island.

The church sign says "all are welcome," but how welcoming they are to sex offenders is an open question. The church's struggle came after a registered sex offender sent an email to the pastor saying that he was moving to the town and wanted to know if he would be welcome at the church. The pastor thought that by setting limits that the man would avoid children and always be escorted by an adult, the issue would not present a problem.

The church sign says "all are welcome," but how welcoming they are to sex offenders is an open question. The church's struggle came after a registered sex offender sent an email to the pastor saying that he was moving to the town and wanted to know if he would be welcome at the church. The pastor thought that by setting limits that the man would avoid children and always be escorted by an adult, the issue would not present a problem. Forgiveness starts this evening

Forgiveness starts this evening Over at the Questing Parson Blog, there is a post Easter conversation between the parson and an Atheist. The Atheist wants to know how the Parson, who he sees as a man of integrity, can preach about stuff like the resurrection which intelligent people don't believe. The Parson has no problem with the resurrection, but he points the man away from things about which he can't be sure and toward things agreed upon, but avoided:

Over at the Questing Parson Blog, there is a post Easter conversation between the parson and an Atheist. The Atheist wants to know how the Parson, who he sees as a man of integrity, can preach about stuff like the resurrection which intelligent people don't believe. The Parson has no problem with the resurrection, but he points the man away from things about which he can't be sure and toward things agreed upon, but avoided:

Kids flower the cross during the opening hymn.

Kids flower the cross during the opening hymn.

Gary is baptized. One of six baptisms.

Gary is baptized. One of six baptisms. Kids still in the moon bounce well after worship.

Kids still in the moon bounce well after worship. Come you all: enter into the joy of your Lord. You the first and you the last, receive alike your reward; you rich and you poor, dance together; you sober and you weaklings, celebrate the day; you who have kept the fast and you who have not, rejoice today. The table is richly loaded: enjoy its royal banquet. The calf is a fatted one: let no one go away hungry. All of you enjoy the banquet of faith; all of you receive the riches of his goodness. Let no one grieve over his poverty, for the universal kingdom has been revealed; let no one weep over his sins, for pardon has shone from the grave; let no one fear death, for the death of our Saviour has set us free: He has destroyed it by enduring it, He has despoiled Hades by going down into its kingdom, He has angered it by allowing it to taste of his flesh.

Come you all: enter into the joy of your Lord. You the first and you the last, receive alike your reward; you rich and you poor, dance together; you sober and you weaklings, celebrate the day; you who have kept the fast and you who have not, rejoice today. The table is richly loaded: enjoy its royal banquet. The calf is a fatted one: let no one go away hungry. All of you enjoy the banquet of faith; all of you receive the riches of his goodness. Let no one grieve over his poverty, for the universal kingdom has been revealed; let no one weep over his sins, for pardon has shone from the grave; let no one fear death, for the death of our Saviour has set us free: He has destroyed it by enduring it, He has despoiled Hades by going down into its kingdom, He has angered it by allowing it to taste of his flesh. That began at Easter, continues in the life of faith, prayer and sacrament and the mission, in the widest and narrowest senses of the word, of the church, and will be complete when justice and mercy flood the whole creation.

That began at Easter, continues in the life of faith, prayer and sacrament and the mission, in the widest and narrowest senses of the word, of the church, and will be complete when justice and mercy flood the whole creation. Rather, what mattered for his early followers was that they continued to know him as a living figure of the present after his death – not just during the forty days of appearances that the author of Acts mentions (Acts 1.3), but in the years and decades (and centuries) ever since. And to affirm, as Christians do, that the living presence of Jesus is Lord is to commit oneself to the story of Jesus as the central revelation of God’s dream for the world. It means to stand against the powers that killed him and to stand for the vision of God’s kingdom that he proclaimed.

Rather, what mattered for his early followers was that they continued to know him as a living figure of the present after his death – not just during the forty days of appearances that the author of Acts mentions (Acts 1.3), but in the years and decades (and centuries) ever since. And to affirm, as Christians do, that the living presence of Jesus is Lord is to commit oneself to the story of Jesus as the central revelation of God’s dream for the world. It means to stand against the powers that killed him and to stand for the vision of God’s kingdom that he proclaimed.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home